Journal of Unification Studies Vol. 20, 2019 - Pages 195-215

This is a substantial revision of an older paper, “Knowledge of God? A Critique and Proposal for Epistemology in Unification Thought,” Journal of Unification Studies 4 (2001-02): 33-42.

The chapter on Epistemology has been considerably expanded in New Essentials of Unification Thought[1] to bring in important correlations from modern neuroscience. However, in its review of the philosophical landscape it deals with mainly 18th and 19th century epistemologies, notably those of Kant and Marx-Engels. It leaves out important 20th century epistemologies arising out of phenomenology and hermeneutics. My concern is that Unification Thought, being so steeped in older epistemologies, is focused on epistemological issues of the past and not those of central interest to philosophers of the present day. It accepts, to its detriment I believe, the materialistic assumption that the main issue in Epistemology is what is the basis of our knowledge of tangible things in the external world. Yet epistemologists have moved on to discuss issues of meaning and interpretation, which surely have direct relevance to Unification Epistemology.

Moreover, because Unification Thought in its current formulations only seeks to answer the questions posed by nineteenth-century epistemologies that ignore the reality of spirit, it, like those older epistemologies, only seeks to ascertain the basis for valid knowledge of tangible objects. Hence, Unification Thought was led to ignore the most fundamental issue for Epistemology, which is to ascertain the validity of our knowledge about invisible and intangible realities. In particular, it ignores the question, how can we know the reality of God?

The Question for Epistemology

The early epistemologies of Bacon, Descartes and Spinoza dealt with the question of how we can have true knowledge in the broad sense. But by the 19th century the field of Epistemology, as represented by the contributions of Kant and Marx, narrowed this quest to the question of how can have true knowledge of things in the external world. As such, they were beholden to and in the service of a nineteenth-century world where scientific investiga¬tion was the primary human enterprise. How can we know that what we see with our eyes is in fact there?

Such a question might help give scientists confidence in the validity of their observations, but it does not answer the question of the validity of knowledge as such. Validity is a major concern of contemporary epistemology, as indicated in its dictionary definition: “the study or a theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge especially with reference to its limits and validity.” (Miriam-Webster)

Modern theories of epistemology go far beyond the limited notion of truth as correspondence: what I perceive in my mind is what is in the world. There is also the coherence theory of truth, which critiques truth-as-correspondence because it ignores the subject’s interpretation of the information that he or she receives. No knowledge, the coherence theory holds, is free from interpretation, or subjective action. Unification Thought covers this issue in axiology, but it is more properly a topic of epistemology. Then there is the pragmatic theory of truth, which evaluates knowledge in terms of its results in the real world. Therefore, in contemporary philosophy, a theory of epistemology, which tests the validity of knowledge, cannot be limited to correspondence alone, but must deal with all these issues.

Furthermore, the narrowly scientific focus of nineteenth-century epistemologies which are conversation partners for Unification Thought’s Epistemology means that the only knowledge to be treated is knowledge of tangible things in the world. Neither these epistemologies nor Unification Thought’s epistemology even think that it is their task to deal with the question of how we can know invisible reality, such as God, or truth, or love. Kant, for example, denies the possibility of metaphysics. So does Marx.

Yet the questions epistemology asks cannot be so limited to things in the external world. Philosophy is the study of all reality; hence it needs to ask the question of whether and how human beings can know all of reality. To begin one’s epistemology with sense impressions ends up leaving out any consideration of knowledge of that part of reality that is intangible to the senses. Yet Rev. Sun Myung Moon teaches that the most valuable realities are precisely those that are invisible: God, love, life, lineage, and conscience.

|

What is more important, that which is visible or that which is invisible? I am sure you realize that the invisible is more important than the visible. You can see and touch money, however you cannot see or touch love, life, lineage and conscience.[2] |

Should the cognition of these most valuable invisible realities not be the main subject of Unification Epistemology? Comparatively speaking, questions about knowledge of tangible things pales to insignificance.

Twentieth-century epistemologies began to investigate the question of our knowledge of invisible realities on several fronts. One is the search for meaning in life, an approach advocated by Viktor Frankl and his students. He claims that meaning arises out of a multidimensional consideration of many perspectives, not only scientific and rational but also psychological and religious. He cites the example of Joan of Arc, who from a scientific perspective would have been labeled a schizophrenic, but from a religious perspective was a saint and from the perspective of French history was a national hero.[3] Each discipline has its own hermeneutics for determining the validity of knowledge. Any quest for an objective, prejudice-free and interpretation-free knowledge is likely to fail. Hence, as Unificationist philosopher Keisuke Noda notes, a Unificationist quest to find valid knowledge should be multi-disciplinary, integrating science and religion.

Furthermore, understanding knowledge from the standpoint of meaning includes the self. While the scientific quest for knowledge brackets the self and looks at knowledge in and of itself, the most meaningful knowledge is transformative of self. Knowledge of the Word can change one’s life; it can bring rebirth.

Therefore, my first contention is that Unification Thought needs to reframe its epistemology in light of the modern philosophical quest for meaningful knowledge. In the application of its epistemology to the FFWPU, it should investigate how people receive truth when they study the Principle, what new meaning it offers them, and how they are transformed by receiving it.

It should go without saying that once Unification epistemology takes the position that the self can be the object as well as the subject of cognition, not only receiving knowledge but also being transformed by it, it can begin to ask about the validity of knowledge of God.

I understand that the standard view of Unification Thought is that God is already present as a basis of epistemology, because God created human beings as microcosm of the cosmos with the elements by which they can have dominion over all things. Thus, the existence of God functions as the guarantee that our perceptions and cognitions will correspond to the objects that we perceive in the outer world.

|

Only when the significance of God’s creation of human beings and all things has been clarified, can the necessary relationship between human beings and all things become clear… Since human beings and all things are in the relationship of subject and object, we can know things fully and correctly. (NEUT, 401) |

However, this limits the role of God to setting up the a priori structure for human beings to experience the world as it is. It does not provide a way for accessing or evaluating knowledge about God Himself, or distinguishing true knowledge of God from false knowledge of God. This is the proper task of epistemology. Given that FFWPU is a movement that advocates for a living relationship with God, should Unification Thought’s epistemology not provide philosophical support for this quest?

Epistemology of the Object Position

Unification Thought uses the human capability to have dominion over all things to explain why “since the human being and all things are in the relationship of subject and object, we can know things fully and correctly.” (NEUT, 401) But in relation to invisible realities like God, love, life and lineage, is the human being in the position of a subject? On the contrary, the individual human being is in the object position. (NEUT, 172-73) This immediately calls into question Descartes’ dictum cogito ergo sum, whether we can know things perfectly, either by experience or by reason.

Consider for example a child in relationship to his parents, in the position of an object. Can he fathom his parents’ heart? If his parents punish him, he may, not understanding their heart or judgment, take it as an act of cruelty. While the parents may have their own limitations, we can assume for the sake of argument that they are trying to raise him with a vision about his future of which he is only dimly aware. How can the child, not being privy to his parents’ mind and heart, have truly valid knowledge about his parents’ intention in their actions toward him? He cannot.

Yet, an epistemology that takes the human being as the subject of cognition places all the standards for judgment within the human being. Thus, in Unification Epistemology the human subject has the prototypes within himself, and the through the operation of the inner four-position foundation in his mind, he collates these prototypes with an external image formed in the brain at the sensory stage. Through this collation method, he arrives at a true judgment of cognition. (NEUT, 402-03) Allowing that this may be a valid understanding of cognition for all things, it certainly does not work for the child who wants to understand truly about his parents. By himself, the child lacks the experience of heart to understand his parents, try as he may. One might say that his prototype of “parent” is not yet developed to that level of understanding. He would do better to take the object position and let his parents instruct him.

In cognition of a higher subject, such as a parent, the child has to enter into a subject-object relationship in which he, as the object partner, is willing to learn his parents’ truth and let that truth be the governing subject for his understanding of sense experience. In the same way, in order to understand God our Heavenly Parent, we study the Word given by God and seek guidance in prayer by taking the object partner position to elucidate the truth as God would want us to know it. Then we let that truth guide our way of experiencing God, while putting aside our own preconceptions.

This is a multi-dimensional give and receive action with the being outside the self, far beyond the method of collation described in conventional Unification epistemology. This is because the self is not the subject of such cognition, but its object. As per Spinoza, we need not only reasoning but also intuition and a spiritual sense to grasp such higher things. (NEUT, 388) In my view, Unification Thought needs to specify such an epistemology in order to defend the appropriateness of receiving God’s revelation through Rev. Sun Myung Moon as valid knowledge that can be the proper foundation for philosophy. There are already elements of that epistemology ready at hand elsewhere in Unification Thought, for example its Theory of Original Human Nature.

The Method of Cognition

In Unification epistemology, cognition of tangible things requires give-and-receive action between subject and object; the human being is the subject and the thing in the world is the object. (NEUT, 402) However, in the cognition of God the positions are reversed: God is the subject and the human being is the object. More precisely, a human being is in the position of mediator between God, the ultimate subject, and all things in the world as objects. Thus, a human being is at the same time an object partner to God and a subject partner to all things in the world.

Nevertheless, since cognition requires a certain amount of subjective action, human beings strive as subjects to cognize God. For this purpose, they use the faculty of intuition. This is not Kant’s intuition of the world, but Plato’s intuition of the cave, according to Dr. Sung-bae Jin. For humans in the cave, who cannot see daylight, the only light they have is reflected off the walls. Human beings can know the light that they see “reflected from God.”[4]

One of these lights is knowledge of God that comes through the conscience. As Kant posited in the Critique of Practical Reason, the voice of God communicates through the human conscience to establish morality. (NEUT, 560) According to Lee, “if our conscience is pure, God will show us through our conscience” what is appropriate behavior for our life. (NEUT, 511) However, this leaves the question of whether one’s conscience is pure. There are many examples of people doing bad things with a clean conscience, because their conscience was conditioned to believe in a faulty standard of goodness. Unification Thought posits an “original mind,” which can overcome the limitation of conscience due to its being conditioned to various standards of goodness. The original mind “possesses God as its standard.” (NEUT, 193)

Unification Thought includes the Theory of the Original Human Nature, which explains that the human original mind is the union of the spirit mind and the physical mind. It states that “when one lives full in accordance with one’s original mind, one resembles the inner four position foundation within the Original Image.” (NEUT, 160) When that resemblance exists, there should be no impediment to direct communication with God.

Spiritual Cognition

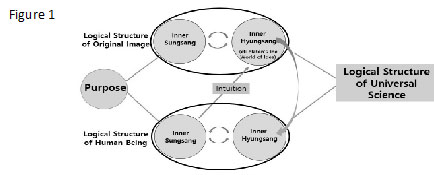

When this obtains, the human being’s original mind, composed of an inner sungsang (the active faculty of mind, of intellect, emotion and will) and inner hyungsang (the repository of ideas, images and concepts), can align with the inner four-position foundation of the Original Image, which likewise is composed of an inner sungsang and inner hyungsang. God’s inner hyungsang is the repository of divine truths, comparable to Plato’s world of Forms. A person’s original mind and God’s Original Image form a correlative base based upon a shared purpose and begin giving and receiving. Then, the person’s faculty of intuition in his or her inner sungsang can fathom some aspect of God’s inner hyungsang, which is then received as an insight or inspiration that comes to reside in the person’s inner hyungsang.

This is spiritual cognition, diagrammed in Figure 1. Dr. Jin calls it the “logical structure of universal science,” which he conceives as a method of inquiry whereby cognition of God’s ideas complements cognition of the natural world.[5]

Having glimpsed intuitively an insight from God’s inner hyungsang, the next step is to secure it as a fully developed concept. This takes place through the process of thinking, which is give-and-receive action between the person’s own inner sungsang and inner hyungsang. In the process of thinking, a person’s inner sungsang makes use of concepts gained through cognition of objects in the world and collates them with the new insight gained from God’s inner hyungsang. In this way, a person fills out that insight and make it into a strong concept, which is relevant to other concepts as well as to one’s actual life. The philosopher or researcher who seeks to penetrate into the truth of God uses both intuition and reason in this manner.

If only we manifested our original nature fully, we would be able to receive insights from God continually, everywhere and all the time. However, because we are still damaged by the Human Fall and its consequences, the operation of intuition is intermittent and not under our conscious control. Often its operation is spontaneous, as when Newton saw an apple dropping and was suddenly given insight about the theory of gravitation, or even unconscious, as when the chemist Kekulé dreamed about snakes biting their tails and woke up with the solution to the structure of benzene.

Cognition from below and from above

According to Unification Epistemology, cognition advances in stages, beginning on the most external, material level and ending at the level of reason and thought. Give-and-receive action between the body’s sense organs and the thing in the external world results in a “sensory image.” Then the sensory image to be collated with prototypes in the body, as governed by the “spiritual apperception” of the human mind, to arrive at cognition at the stage of understanding what the object is. Later refinements in cognition can come through practice and reason.

Here, Dr. Jin extends the process of cognition to include intuition by which the mind can glimpse realities in God’s inner hyungsang. This is both a bottom-up process, pursued by the researcher who seeks from the depths of Plato’s cave, and a descent of truth as a flash of inspiration from the higher mind of God to the earthly person. Like Jacob’s dream of angels ascending and descending a ladder (Gen. 28:12), knowledge can flow downwards from heaven to the self and upwards from the self to heaven.

This is what is called spiritual cognition. According to Exposition of the Divine Principle,

|

Cognition of spiritual reality begins when it is perceived through the five senses of the spirit self. These perceptions resonate through the five physical senses and are felt physiologically. (EDP, 103)[6] |

In this description, spiritual sensation precedes physical sensation. The “sensory image,” to use Dr. Lee’s term, arises after the spiritual image has impressed itself upon the spirit mind, which then by means of resonance causes an image to form in the mind of the physical self. This implies that understanding, even thoughtful knowledge, can precede cognition through the senses. Flashes of insight or intuitions are often cognitions of this type. Even cognition of issues in human relationships can arise from such invisible feelings and intuitions.

How much of cognition in human relationships occurs as invisible feelings impressed upon the senses in a top-down process? Love, for example, is a spiritual feeling which colors a person’s perception of the beloved’s eyes, face and even her scent. Dr. Lee spoke about love in the spirit world as filled with light.[7] On earth, one’s beloved may appear “radiant.” This is not necessarily because she is materially giving off light, but because God sends His Light of love into her, which her lover perceives with his spiritual senses. These resonates with his physical senses to produce a sensory image of her glowing with light. Thus, perception of the spiritual radiance of love by the physical senses occurs at the end of a top-down process that began in God.

Fallen people, despite their infirmities, have made great efforts to know God and receive information from Him. While one path is to search and search to grasp at truth, we also have the guidance of religion to empty ourselves and put ourselves in the object position. Unification Thought calls this “object consciousness”:

|

The fullness of God’s love comes to be felt only by those who have perfect object consciousness―that is, the heart to attend God and to be thankful to God. No matter how sublime God’s love may be, those who lack a sense of object consciousness will never feel a sense of fullness; instead, they will continually feel dissatisfaction. (NEUT, 288) |

By emptying ourselves of self and cultivating object consciousness, we can come closer to God. (NEUT, 191) to be able to receive what God, the Subject Partner, wishes to give. Taking the position of an object partner, we want to open ourselves to receive what God wants to give, whether praise or blame, warning or encouragement, or direct guidance.

Another aspect of knowledge of God that is normally received from above rather than grasped from below is knowledge of God’s Heart, which lies within God’s inner sungsang. God takes the initiative here, to communicate an element of His inner sungsang: His Heart, His Will, His joy or sorrow, down to the person’s inner sungsang. This is what takes place during prayer and meditation. It is the essence of pure religious experience. When we put ourselves in the object position, we can intuitively sense God’s will for us and make ourselves available to be of use to God as His instrument.

Spiritual Growth to Resemble God

For a being in the object position to God, the fundamental prerequisite for knowing or cognizing God is to first resemble God. Human beings were created in the image of God, but the image of God is damaged in fallen humans. Lacking perfect resemblance, it follows that fallen humans cannot expect to know God in the fullest sense.[8] Traditional philosophies assume ordinary human nature to be adequate to cognition. This surely cannot apply to knowledge of God. The fact of human fallenness should even shake our naïve certainty that the mind has an adequate foundation for scientific investigation into all things—given that even creatures have a spiritual dimension that fallen man can at best only dimly perceive.

Divine Principle speaks of internal spiritual growth, achieved through fulfilling the Foundation of Faith and Foundation of Substance, as a prerequisite to becoming a “perfect incarnation of the Word.” The concepts of “individual embodiment of truth” and “object partners for the joy of God” are also relevant to this discussion. (EDP, 28, 33, 179) These concepts speak to the inability of human beings to cognize rightly without first developing themselves, through a portion of responsibility, to reach a state of resemblance to the divine image. Therefore, a philosopher first needs to cultivate his or her self with spirit and truth before he or she is really qualified to consider the epistemological question concerning the validity of knowledge about God.

Unification Thought’s theory of human growth is found in its Theory of Education. Of particular relevance for our purposes is its discussion of Education of Heart, which, in addition to providing content about God’s heart, describes the essential role of parents and teachers in fostering the child’s relationship to God. (NEUT, 250-58) However, growth in one’s relationship to God is a continual process throughout life. In this regard, Unification Thought needs to develop a theory of growth. More needs to be elucidated about the prerequisites for growth and the process of growth in terms of give-and-receive action with God, externally with people, and internally within the original mind.

The Role of Religion

Here is an argument for religion and the requirement of faith in order to grow in knowledge. Fallen humans may not be in a position to have sure knowledge of God, but growth in knowledge of God is possible by following a spiritual path, which humans take up by faith. Central to growing to resemble God and thus have better knowledge of God is to live by God’s Word, which is received in faith, not as certainty. In the Bible, the first knowledge was given to Adam and Eve as a commandment. Faith is an important component in attaining knowledge of God, for it enables people to stand in the object position to God.

The revelations of religion, which are the basis of faith, do not always agree. Nor are they always interpreted in ways that lead to human betterment. Exposition of the Divine Principle admits there are portions of the truth that even it does not elucidate. (EDP, 12) The truth revealed in sacred scriptures, while often helpful, is not complete knowledge. Nevertheless, at least the paths of faith, while relative, can be appreciated for leading seekers towards greater degrees of resemblance to the Divine Image. They need not be affirmed as absolute in every respect, as long as they contain kernels of truth that people can at least rely on as the rungs on a sturdy ladder of spiritual growth. Revelations and scriptures function like a textbook or a schoolteacher, pointing to truth beyond itself, as Paul taught, “The Law was our tutor to bring us to Christ.” (Gal. 3:24)

However, some skepticism about religious texts may be a positive thing, in that it keeps the philosopher seeking for ever deeper understanding. Even the path that many Unificationists walked to arrive at the Divine Principle included a period of doubting the revealed truths of the Bible and the Christian religion. It opened their minds to be receptive to the Principle’s higher and deeper truth. It also opened their spirits to being directly guided to a place that they had not conceived of during their earlier Christian life. That sort of constructive skepticism, when it is the product of sincere searching and not merely an expression of egoism, serves a deeper faith—faith beyond dogmas and sacred texts, lived in relationship with God who is personally guiding our lives.

This leads to the insight that true knowledge cannot be fully expressed in the propositions of faith; it must be lived. True knowledge is embodied knowledge. Attempts by philosophers to arrive at an adequate epistemology based upon either empiricism or rationalism or a unity of the two schools misses this important point. It was well known by the masters of Zen, who regarded cognition as the enemy of truth. Cognition, sensations, reason, theory—these are obstacles to truth when they lead people to think they know when they don’t know. They hide a fundamental truth about knowing God, and knowing the self, that we are required one to stand in the position of an object, with object consciousness.[9]

Spiritual Growth in the Family

Beyond religion, the original design of creation provides for growth by placing human beings in the context of family. The family is intended to be the seedbed for the growth of individuals with knowledge of God. This is Rev. Moon’s teaching of the Four Great Realms of Heart, which was added as an appendix to New Essentials of Unification Thought. (NEUT, 534-543) The Four Great Realms of Heart trace a path for the growth of love in the family, from children’s love to sibling love, conjugal love and parental love. Such love cultivated in the family helps us to develop into people of love who fully resemble God, since God’s fundamental essence is love.

Whether or not God is invoked and recognized, this course of growth of love develops an individual into God’s object partner:

|

These four kinds of love, namely children’s love, brothers and sisters’ love, husband and wife’s love, and parents’ love, are all practiced under God’s love; therefore, all the family members can… regard God as their object partner of love consciously or unconsciously. (NEUT, 538) |

The growth of love in the four great realms of heart supports our resemblance to God in another way, by having us travel a course of development that was already in God’s mind before He created the first human beings:

|

The image of children being born and growing as brothers and sisters, and becoming husband and wife and then parents, namely, the phenomena that human beings are born and grow, while experiencing love step by step, take place first in heaven or, more precisely, within God’s mind. That is to say, the growth of children, growth of brothers and sisters, becoming husband and wife, and then becoming parents first takes place in an ideal form in God’s mind before they appear on earth. (NEUT, 540) |

Moreover, these four great realms of heart are the foundation for love beyond the family: love of nation, love of humanity and love of nature. (NEUT, 539) God’s love has such a quality that it expands universally.

Although the current textbook of Unification Thought places this discussion of the four great realms of heart in an appendix, in my view it should be integrated into the standard chapters of Unification Thought, most likely the Theory of Education. Moreover, there is the connection to Epistemology that is our chief concern here, in that resemblance to God is a necessary condition for sure knowledge of God.

Cognition in the Context of Family

Humans are social beings, who use language and create meaning in the context of social groups. The starting-point of philosophy is language, the naming of things. Through language we express concepts about the things we perceive for the sake of others in the group; in other words, we create knowledge. The knowledge we create has purpose and meaning in the context of that social group. The social group is a space for shared interpretations and meanings that specify what knowledge is.

A human being’s primary social group is the family. In Unification Thought, the family is the primary locus of human growth and meaning. In this light, we should consider that the primary context for philosophical reflection on the validity of knowledge may not be the individual but rather the family. Therefore, Unification Epistemology might profitably treat cognition not as the action of an individual sitting alone, but as a process that takes place in the family context and a social context. This will involve it in discussion with contemporary philosophers of hermeneutics.

Cognitions in the family are well rounded. They occur when family members are both in the subject position and the object position. Knowledge enters from both directions, indeed from all directions as the individual relates to others situated above and below, right and left, front and back. In a family, people ascertain the validity of their knowledge by how well it coheres with the views of other family members whom they live with and love, and whether the practice of that knowledge is upbuilding of the family and regarded as praiseworthy within the family circle.

Although we may have thoughts and feelings as individuals, we need the stimulation of giving and receiving with others, especially those we hold dear, who can confirm, disconfirm, or cause us to adjust our thinking. Knowledge in the family is rounded, encompassing heart as well as intellect. The family is the locus of love, life, lineage and conscience—all invisible realities—which are made plain through the give and take of family relationships.

During the course of restoration, sages and philosophers often searched for truth in solitude. This was true of saints like Buddha and Jesus, and also of philosophers like Socrates. Kant continued this tradition of solitary philosophizing, as did Kierkegaard. Solitude was the best environment for introspection and rational thinking. However, now that the world has entered the Cheon Il Guk Era, philosophy is free to function in the natural setting of family in which God created human beings to abide. Perhaps Unification Thought should now develop from a starting-point that regards the individual as embedded in family relationships.

The same is true for knowledge of God, sought for through religion. Religions heretofore spoke of the individual standing before God. However, now we know that God is our Parent, and as such He-She is a member of our family, who loves us and who elicits from us attendance and filial devotion. Yet, until God enters our family, how can we access God’s thoughts that arise when God meets us in all our various family relationships? Even God cannot access all His-Her thoughts and feelings as a Parent if there are no human beings to give and receive with God as children, as spouses, as siblings, or as parents. It is through our relationships with God as object partners in every position that God becomes real to us, and our knowledge of God becomes as real as the noon-day sun.

Standard of Judgment for the Cognition of God

Prototypes

Dr. Lee advances a theory that prototypes, which are “content in the mind of the subject,” serve as the standard of judgment in cognition” to which external sense data is collated. (NEUT, 404-05) These prototypes have their origin in the subconsciousness of the cells of the body. That is, they are a property of life, or mind at a lower level. (EUT, 407-10) The theory of prototypes may be adequate to provide a basis for cognizing material things, which all were created in the image of a human being. But can they provide the basis for knowledge of God?

The answer is yes, because God designed the human being, both the mind aspect and the body aspect, to resemble Him and to relate with him. Thus, the Divine Principle declares that God relates most intimately to human beings, above all other forms of life. Human beings, alone in all creation, have sensibility to God’s heart and can know God’s will. (EDP, 80) Human beings alone possess the spiritual elements to be rulers over the spirit world. (EDP, 46) Accordingly, the prototypes in the human mind should be sufficient for cognizing God.

This logic presumes the view of God revealed in the Divine Principle, who is a personal God. It follows from the Bible’s statements that God created human beings in God’s own image. (Gen. 1:27) From the point of view of God’s purpose of creation, which is to have an object partner of love, God has to be a personal God. From the point of view of Unification Thought’s Heart Motivation Theory (NEUT, 33), only a God who can share love with human beings will suffice to explain why God created the universe, and such a God must be a personal God. From the point of view of Unification Thought’s Theory of Original Human Nature, by which human being is a being of heart, only a personal God will suffice: “Heart is the core of Sungsang, and therefore the core of God’s personality.” (NEUT, 164) It is not my intention here to review the theological arguments for why the highest concept of God is that of a personal God, rather than some sort of impersonal infinite entity that deigns to relate with human beings by lowering Itself to the level of personhood.

Furthermore, although the prototypes arise out of “protoconsciousness,” which is a property of cells of the human body, (NEUT, 407) they operate in the original mind, which is the unity of the physical mind and the spirit mind. Hence, images and cognitions that form in the physical mind by collating with prototypes that originate in the body then engage in give-and-receive action with the spirit mind. By resonance between the spirit mind and the physical mind, cognition reaches upward to God, and concepts, ideas and feelings from God reach down to affect the body.

Thus, cognition of God is a unified cognition of spirit and body. This is true of spiritual cognition generally. What is sensed by the spirit’s five spiritual senses comes into conscious awareness when they resonate with the body’s five physical senses. (EDP, 49)

However, although prototypes proved a general structure within which God can be cognized, they are not adequate to guarantee accurate or valid knowledge of God. This is because, as was previously mentioned, human beings are not in the position to have dominion over God, as they are beings whom God created. Furthermore, in relation to God, human beings are in the object position. Accordingly, God set up a certain course of growth for human beings and gave them responsibility to perfect themselves as the condition for arriving at the state of complete resemblance.

Therefore, the prototypes cannot be the standard of judgment for cognition of God that will yield valid knowledge. Consider that a child with undeveloped internal images of the world (prototypes) cognizes the world differently than does an adult. The child has a sort of knowledge of the world, but can it be said to be valid or certain knowledge? It is not likely that his parents will agree, based on their experiences and more highly developed internal images. In the example with which I began, the child misunderstands the parent’s discipline as cruel punishment because he has no experience of the parental heart. His limited store of prototypes can recognize some types of love, but not others. If we go back to Bacon’s original aim to come to certain knowledge by dispelling one’s prejudices, then certainly these malleable prototypes, which may be influenced by the narrow experiences of life, must be classified as “idols” (NEUT, 384) that can hardly be trusted as a standard for judging the validity of higher knowledge, specifically knowledge of God.

This brings us back to the question of the validity of knowledge—the major question in epistemology. What can be the basis for knowledge of God of which we can have confidence that it is correct knowledge?

The Standard of Judgment in Axiology

For help in answering the question of what can be the standard of cognition in Epistemology, we can turn to Unification Thought’s theory of Axiology. Although many philosophers, following Kant, have separated fact: “the rose is red” from value: “the rose is beautiful,” they are not necessarily separate issues. As Lee states, the result of this separation has been “many problems.” (NEUT, 239) Unification Thought should not follow this mistake of Kant. Trueness is a value, according to Lee, which satisfies the intellect. Therefore, we cannot so tightly distinguish Epistemology, which aims for valid knowledge, from Axiology, which aims for absolute value—including absolute truth.

The process of actualizing “value” in Axiology is a give-and-receive relationship quite akin to what is described as cognition according to the theory of Epistemology. As cognition is a process of collation through giving and receiving between pre-existing prototypes within the human subject and sense-images from the world (object), the determination of value is another sort of collation that matches the certain elements of the human subject with the qualities of the object.

However, unlike cognition of things in the world, which appears to be a universal process because the prototypes that are based on the human body are the same for everyone, in the determination of value people’s subject elements may differ considerably from one person to the next. A person’s subject requisites include desire, interest, a particular view of life, subjective taste, etc. All of these are brought into play when appraising the value of an object. An object’s requisites include its purpose, utility, beauty, form, etc. However, different people will appraise its value differently based on their different subject elements by which they engage in give-and-receive action with it. (NEUT, 210)

Thus, the example of the child being punished, the child’s perception of his parents’ motives at the time of his punishment is an act of cognition, but at the same time it is an act of assigning value. In the latter, it is a valuation of the parents based on the interplay of the child’s “subjective requisites,” including his conscience and desire for affection, and the parents’ action to punish. A child with a more developed conscience may see his parents’ action more favorably—and even feel grateful for being corrected, while a child with a less developed conscience may misunder¬stand his parents’ heart and think them cruel. In both cases a cognition is formed, but the cognition is very different. This is because the cognition is also an act of assigning value, and for this, the subject’s requisites are of prime importance.

Unification Axiology proposes God’s love and truth as the absolute standard for appraising value. (NEUT, 215) As mentioned, the standard for appraising value applies to the subject, the human being who is giving and receiving with an object. The object satisfies the human being’s desire based upon the human being’s appraisal of its value. In the process of appraising value, the subject brings his or her standard of value, which is often based in beliefs and religion. However, Unification Thought rejects the relativism of the multiplicity of religions and argue that there is just one God and just one standard of value, in which the standards of all religions cohere. Therefore, as the world heads into the Cheon Il Guk Era, religious differences will lessen and people will recognize the shared truths of all religions. When people adopt these truths and apply them to valuing other people and things, they will apply what approaches the absolute standard.

For example, God’s love at the level of brotherly/sisterly love is indicated in Christianity by love of neighbor, in Buddhism by mercy, and in Confucianism by jen (human-heartedness). All of these loves cohere, leading to an absolute standard for God’s love at the level of brotherhood. This becomes the standard by which all people should treat others and value others. Or to take another example, since God created the universe, the truth and principle by which He created is unique, eternal and universal. It is the principle of living for the sake of others (NEUT, 215), or in Wolli Wonbon, the Principle of the Object Partner. As people of every religion live by this truth, they will value others based upon its absolute standard.

Thus, Axiology places God’s love and truth squarely within the subject requisites of the person adjudicating value. Accordingly, the a priori elements for assigning value and meaning to any sort of higher, invisible reality, be it love, life, self, truth, or God, are heart-felt convictions about God, love and truth in the subject making the valuation. As the person matures in her understanding of love, life, self, truth and God, these subjective elements approach the absolute standard for appraising value. It should be the same with Epistemology. The a priori elements in the subject for cognizing any sort of higher, invisible reality, be it love, life, self, truth, or God, are heart-felt convictions about God, love and truth in the subject that should apply when making the cognition.

Unifying Epistemology and Axiology

Accordingly, Epistemology and Axiology need to be unified in order to overcome the division between fact and value. Modern Epistemology is not restricted to the question of the correspondence or coherence between things in the world and cognitions in the mind, but also asks questions about the validity of knowledge: is it meaningful, truthful, and accurate as to heart and purpose? Validity in this sense has to do with value. In this sense also, the elements of Axiology are needed if Epistemology is to speak meaningfully about the validity of knowledge about God.

Thus, Kierkegaard critiqued Hegel’s rational and systematic explanation about God and His manifestation in the world and in history as inadequate. Beyond the rationalist approaches, Kierkegaard taught that one comes to understand God in the true sense only based on one’s personal relationship with God, which he believed requires a leap of faith. The process by which people understand God takes place not primarily as an act of the intellect but involves the whole person: intellect, emotion and will, and especially heart. This is because human beings are more than rational beings; they are beings of heart.

Keisuke Noda contends[10] that to come to true knowledge of God in a relationship of heart, human beings need to become God’s object partners, who in the language of the Divine Principle, are individual embodiments of truth. (EDP, 20) Moreover, human beings are meant to dwell with God in the realm of God’s direct dominion, where they can freely share love and beauty with Him-Her. (EDP, 20) For this, human beings need to grow, especially by cultivating their heart, in order to manifest God’s nature. That being so, when it comes to Epistemology, do people who have yet to fully become God’s object partners or dwell in God’s dominion have as profound an understanding of God as people who have attained this level?

It follows that for Unification Epistemology to deal with the question of the knowledge of God, and particularly if it is to determine the validity of such knowledge, it needs to incorporate elements from Axiology. In particular, the standard for cognition of God cannot be limited to only the prototypes in the mind that are based on the human body, but should also include the subject requisites that develop in the course of growth towards becoming an individual embodiment of truth, which takes place within a relationship to God. This is also the case for correct cognition of other subjective beings: human beings and even our own selves.

When Epistemology goes beyond the question of knowledge of things in the material world to deal with knowledge of higher beings, beings with minds, we need to reckon that God, whose love and truth is the standard of judgment in axiology (NEUT, 215, EDP, 37), must also be the standard of judgment in Epistemology. Even if people are not at the level to know God fully, they should be equipped with the elements of love and truth that arise in the course of spiritual growth in religion, in a loving family, and through life experience where they develop a relationship with God. We need these additional elements to be operating in our original mind in order to appraise our knowledge, even our cognitions, of subjective beings including God, ourselves, and other human beings. This unification of Epistemology and Axiology that I am suggesting will help Unification Thought overcome the division between fact and value, science and religion.

Knowledge: The Goal of Cognition

One way to quickly get beyond the dichotomy of fact and value is to specify the standard for the validity of knowledge. The goal of cognition is knowledge, but knowledge is not simply information. Unfortunately, NEUT does not define what is knowledge; this is a weakness. Epistemically, we would want knowledge to be true (corresponding with reality), coherent (consistent with the best interpretation), and pragmatic (of benefit to the individual, the family, the world and God). In other words, we want it to be valid in every respect.

Unification Thought can provide a basis to define knowledge and to specify the standard of knowledge: Knowledge is a representation of some element of the Logos. Before creating the universe, God developed the Logos as His plan of creation. The structure of the Logos is already specified in Unification Thought in the Theory of the Original Image. (NEUT, 27-33). In particular, it is an entity composed of dual characteristics. They are the dual characteristics of sungsang and hyungsang, and masculinity and femininity. I note that while NEUT’s description of the logos focuses on the dual characteristics of sungsang and hyungsang, Exposition of the Divine Principle emphasizes the dual characteristics of masculinity and femininity. (EDP, 170-71)

In considering knowledge, the hyungsang aspect is fact and the sungsang aspect is value. Thus, the hyungsang aspect is cognized through collation with prototypes, while the sungsang aspect refers to value that is appraised through the subject’s action of interpretation. The give-and receive action between the sungsang and hyungsang poles of knowledge links fact with value. Sungsang contains the aspects of emotion, intellect and will; therefore, knowledge has all these elements. By elucidating that knowledge contains both sungsang and hyungsang, Unification Epistemology can unite fact and value.

Knowledge also has the dual characteristics of masculinity and femininity. Since women are in a different position than men in terms of Ontology, they must also be in a different position as regards Epistemology. It is known that women’s brains are wired differently from men, and women perceive the world differently than men do. Women are said to have a better grasp of emotions than men and a superior faculty of intuition for dealing with other people. A growing body of scholarly evidence suggests that women think and theorize differently from men.

This means that in cognition, especially in the subjective action by which a fact is freighted with interpretation and meaning, there is both a masculine and a feminine perspective. However, since it is mostly men who do philo¬sophy, laboring as they do under the arguable assumption that epistem¬ology is a generic human activity, they inadvertently elevate the male way of looking at reality and discount the feminine viewpoint. I would hope that in the future more women would contribute their thoughts and insights to the development of Unification Thought, including Epistemology, to clarify these gender differences and come to a more comprehensive understanding of knowledge.

When God formed His Logos before the Creation, He operated out of heart and purpose. Therefore, all knowledge has the elements of heart and purpose. Knowledge is sought after by human beings with purpose, and it ends up carrying that purpose within it. This is why science cannot be divorced from values, and the acquisition of scientific and technological knowledge cannot be separated from the uses to which it is put. It is a sorrowful fact that the primary motivation for technological progress and the advancement of scientific knowledge through history has been war and the quest for ever more deadly weapons. When purpose is not adequately addressed, even knowledge that is created with the best intentions ends up being misused for corrupt purposes. Yet the ultimate purpose of all knowledge should be love, in accordance with God’s original heart of creation.

As God’s Logos is centered on God’s heart, human knowledge should be centered on heart. Human beings are most essentially beings of heart, which encompasses intellect, emotion and will. Even the word “mind” in the Korean language includes the dimension of heart. Often, the heart can be a warrant for validity of knowledge, even when the intellect is unsure of all the facts of a matter. Such is the case with knowledge of God. Heart is the best starting-point for discussing knowledge of God, which is most essentially knowledge of the heart.

Conclusion

Unification Epistemology needs to go beyond the nineteenth-century problem of how we can have knowledge of external objects in the world—an issue that arose because of the world’s preoccupation with science—and deal with modern issues in Epistemology regarding the validity of knowledge. Validity of knowledge includes not only correspondence to the world but also coherence and meaning. In this regard, Unification Epistemology needs to recognize the requisites of the human subject that come to play in interpretation. This topic is well covered in Unification Thought’s treatment of Axiology. I recommend that Axiology and Epistemology be unified in Unification Thought. This will elevate the discussion of Epistemology to deal with issues of meaningful knowledge and valid knowledge—topics that are current in philosophy today.

I also suggest, as a step toward this end, that Unification Epistemology define the meaning of knowledge in accordance with the structure of the Logos, which has dual characteristics centering on purpose. It should not simply equate knowledge with facts, which is a secular and materialistic definition of knowledge that leaves out the sungsang aspect. A full and complete definition of knowledge should reflect the content of the Logos, which is based on the Original Image. This meaning of knowledge includes both fact and value. It includes both male and female understandings. It goes beyond intellectual knowledge to include knowledge of heart.

These steps lead us the core of this essay, which is to address, from the point of view of Unification Thought, what I take to be the most pressing issue of Epistemology: How we can arrive at valid cognition of God? What or who is God that we can know? Are human beings created such that we can know God fully? Or should we say that while God is ultimately unknowable, there are some aspects of God that we can know, because God Himself wants to make a relationship with us as our Parent? In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant sought a basis for validity of knowledge about God, and concluded that it did not exist. Nevertheless, I believe that Unification Epistemology, rightly conceived, can address this issue and come up with solutions.

To explore the validity of knowledge about God, it is suggested that Unification Epistemology treat the human being both as a being in the subject position and a being in the object position. It should treat the human being as the subject of cognition who imputes value, but also as the object of cognition who is valued. It should recognize that knowledge is not formed by solitary individuals, but always within family and social contexts where meaning is conferred and validity appraised.

Moreover, since it is as an object partner of God that one grows in knowledge of God, of love, of conscience, etc., the human being in the position of object partner needs much more attention. In this regard, Unification Epistemology must unavoidably address the issue of revelation, particularly since the revelation of the Divine Principle is given as the fundamental authority for Unification Thought’s self-understanding of its validity as a philosophy.

Notes

[1] Unification Thought Institute, New Essentials of Unification Thought (Tokyo, 2006). [Hereafter NEUT]

[2] Sun Myung Moon, “In Search of the Origin of the Universe” (September 15, 1996), PHG 2.3, pp. 215-16.

[3] See Keisuke Noda, “Multi-Dimensional Hermeneutics for the Integration of Knowledge: A Preparatory Analysis for Unification Hermeneutics,” Journal of Unification Studies 18 (2017):139-156

[4] Seong-bae Jin, A New Renaissance: Systematizing the Academic Studies of Godism, abridged edition (Sun Moon University Press, 2019), p. 71

[5] Jin, A New Renaissance, p. 74

[6] Exposition of the Divine Principle (New York: HSA-UWC, 1996) [Hereafter EDP]

[7] Sang Hun Lee, Life in the Spirit World and on Earth (New York: FFWPU, 1998), pp. xiii, 60

[8] In Unification Thought, knowledge of God means especially knowledge of the Heart of God, an understanding that is as much emotional as it is intellectual. Therefore, even under the Augustinian premise that the Fall damaged the faculties of will and emotion but not intellect, our ability to know God is still impaired.

[9] See Keisuke Noda, “Understanding the Word as the Process of Embodiment,” Journal of Unification Studies 1 (1997): 55-70

[10] Keisuke Noda, “Understanding God: The Conceptual and the Experiential in Unification Thought,” Journal of Unification Studies 4 (2001-02):7-16